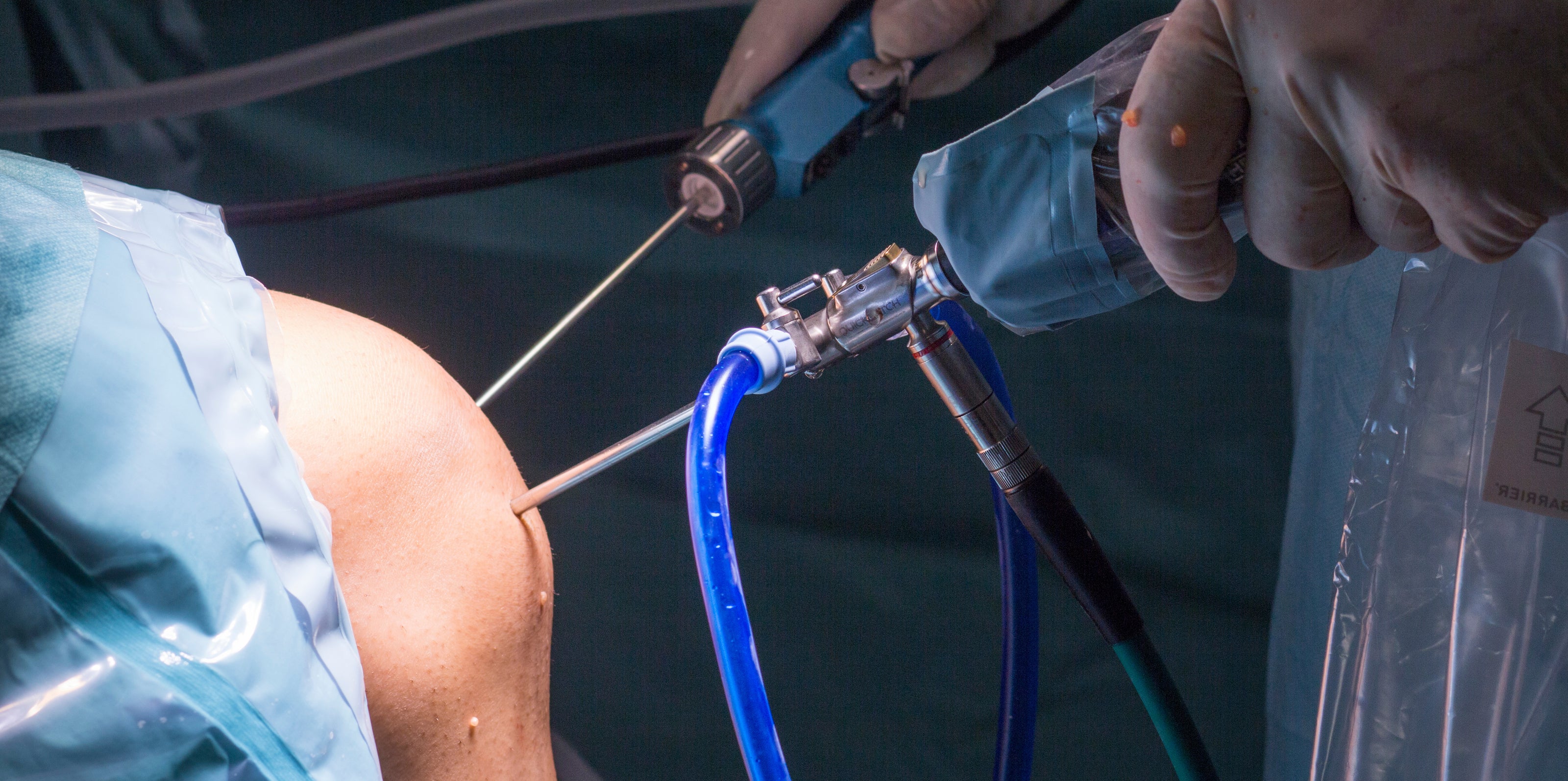

Knee Arthroscopy Cartilage Surgery

When symptoms persist or the cartilage damage is more extensive, surgery may be needed to restore joint surface integrity, reduce pain, and improve function. The goal is to either preserve the remaining cartilage or regenerate new tissue to protect the knee from long-term wear.

-

When symptoms persist or the cartilage damage is more extensive, surgery may be needed to restore joint surface integrity, reduce pain, and improve function. The goal is to either preserve the remaining cartilage or regenerate new tissue to protect the knee from long-term wear.

-

Arthroscopic Debridement

This is a minimally invasive keyhole procedure where rough or frayed cartilage is smoothed and any loose fragments are removed from the joint. It can help relieve pain and improve movement, particularly in milder cases or in combination with other treatments. While not a long-term solution for larger defects, it may reduce mechanical symptoms like catching or locking.

-

Microfracture

During microfracture surgery, small holes are created in the bone underneath the damaged cartilage area. This allows blood and bone marrow cells to enter the defect, forming a clot that eventually develops into fibrocartilage, which can reduce pain and improve function. It’s typically best suited for younger patients with smaller, well-contained lesions.

-

Minced Cartilage Procedure

This single-stage arthroscopic procedure uses a small amount of your own healthy cartilage, usually harvested the periphery of the defect or from a non-weightbearing part of your knee. The cartilage is finely minced during surgery and applied directly to the damaged area. It is secured using a biological glue or scaffold, encouraging the growth of new cartilage-like tissue. This technique is increasingly popular for medium-sized lesions, especially in younger, active individuals, and has the advantage of being done in one operation without needing lab processing.

-

Osteochondral Grafting (OATS / Mosaicplasty)

In this procedure, small cylindrical plugs of bone and cartilage are taken from a healthy, non-weightbearing area of your knee and transplanted into the damaged site. This technique restores the surface with actual cartilage and underlying bone, making it suitable for moderate-sized defects. It offers immediate structural repair and good durability, particularly for focal cartilage injuries.

-

Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation

In cases where the cartilage defect is large or involves significant bone loss, an allograft (donor cartilage and bone) may be used. The graft is carefully matched and shaped to fit your knee. It allows restoration of both cartilage and underlying bone in a single procedure. It avoids the need to harvest from your own knee, which is beneficial when treating larger areas.

-

Scaffold-Based Implants

These are newer techniques that use synthetic or biologic scaffolds designed to support and guide the growth of new cartilage. The scaffold may be used on its own or combined with cartilage cells or stem cells. These procedures are still evolving, but they offer promising options for treating larger or more complex defects while preserving as much of the joint as possible.

-

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Recovery depends on the type of procedure, but all cartilage surgeries require a structured rehabilitation programme. Weight-bearing and activity are gradually reintroduced under physiotherapy guidance to support proper healing and return to function. Full recovery may take several months, especially after more advanced cartilage restoration procedures.

-

Your Personalised Treatment Plan

As a knee surgeon, I tailor treatment to your needs—whether you're managing day-to-day symptoms or aiming to return to sport. After a full assessment, I’ll help guide you through the most suitable treatment path to protect your joint and support long-term knee health.